Prompted by an Art Magazine Two Innovators Created a New Class of Numismatic Items

Not often is a new class of numismatic items born. We have seen this only twice in the last fifty years. The most recent is the bullion item – coins and medals struck solely for their precious metal content.

December 2015 is the fiftieth anniversary of the other, an entirely new numismatic genre that has swept the world for its popularity among medallic artists. This class of medals is unique to the numismatic field – the medallic object.

Created in the art world, but produced in the medal world, it was a marriage that occurred among three New York City institutions. Not an accident, it was a concept created by an art magazine, an art museum curator, and an art medal manufacturer. For medallic objects are an art creation, the mating of modern art with medallic form.

As a Christmas gift promotion in 1965, Art in America magazine wanted to offer its readers something available nowhere else. Their relationship with the leading artists of the time prompted them to promote a new format bas-relief created by top sculptors, yet in a size suitable for intimate display.

The magazine’s officials commissioned a curator of modern art at New York’s Whitney Museum, Edward Albert Bryant, to manage the project. He contacted the most prominent sculptors in the modern art field. Seven accepted his challenge – to create a modern art work that could be made in a small size.

Ernest Trova “Falling Man”

The variety of their creations expressed their current work. Sculptor Ernest Trova, for example, was at the time creating a series of major sculptures in a series best described as “Falling Man.” How to transfer this concept to a smaller venue?

Trova solved this with a brilliant design of seven human figures aligned inside a circle with a bright red enameled arrow pointing with a subtle thrust of a Man in downwards motion — no matter how the piece was rotated. He added a legend in a raised panel circumscribing the rim.

His design met the form of a medal but was unlike anything ever produced before. It was the birth of a new sculptural work in medallic form, embracing modern art in a new class of numismatic items. A class that was to remain unnamed for two decades.

Harold Tovish “Meshed Faces”

Six other sculptors created models where their imagination and mannerisms ran unfettered. Boston sculptor Harold Tovish interspersed two human heads he called Meshed Faces. His anepigraphic design denoted a dehumanization of our modern culture with mechanical forms.

Once curator Bryant had models in hand he sought a way to replicate them. His search did not take him far as he found nearby Medallic Art Company ideal for the task. He met with the firm’s president, William Trees Louth.

Edward Bryant and Bill Louth

The two men pored over the models discussing how best to make the final items. Accustomed to striking the company’s medallic output, Louth suggested striking the items in medallion size. Bryant wanted something larger since dies at that time were limited to no greater than five-inch diameter. The obvious answer, Louth proposed, was making them each as electrogalvanic casts – galvanos.

Once the size decision was made, Louth further suggested striking several as conventional medals, and creating even a smaller size as a pin that could be worn. Bryant was elated at those suggestions.

Tovish’s model then could be made as a 12-inch galvano – which Art in America called “wall piece” – a 2¾-inch medal called a “desk piece,” and a 1-inch “jewelry pin.”

Tovish’s model then could be made as a 12-inch galvano – which Art in America called “wall piece” – a 2¾-inch medal called a “desk piece,” and a 1-inch “jewelry pin.”

Next discussion was the finish to be applied to each. Every design had to have a distinctive patina. Here, they felt, the artist should have some say to ensure the final work adhered to the artist’s original vision.

While Louth entered orders for his craftsmen to commence producing the items, Bryant wrote the article “Christmas For Connoisseurs” for the magazine, with full-page color illustrations of the seven avant-garde items.

The article appeared in Art in America’s December-January 1965-66 issued to be in readers’ hands during the gift-buying season. At the back of the magazine, among small gallery ads, was published a full-page ad offering the seven items for sale.

Constantino Nivola “Loving Couple”

The ad touted “An Exceptional Collecting Opportunity. Relief Sculptures in Limited Editions.” The work of all seven artists – well-known to the magazine’s readers for their reputation and celebrity status – were offered as Wall Pieces (galvanos), medals, and pins. Only two artists’ creations were offered in all three options: Tovish’s Meshed Faces, and Constantino Nivola’s impressionistic Loving Couple, an expression of Man and Nature beneath a dream cloud.

Four of the seven items were issued in circular form. In addition to Tovish’s Meshed Faces. Elbert Weinberg, working in Rome, submitted his Salome in four dancing poses within the circular format. Perhaps his creation could be considered humanistic as it displayed four human figures.

James Wines

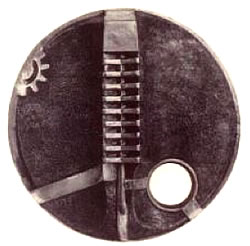

The design by James Wines, known for expressing architectural influence in his sculptural work at the time, continued this theme in the medallic rendition. His design was the only one with open work, a small aperture near the lower edge.

Roy Gussow created The Flow of Water over the Edge of a Pool. Bryant described it in modern art language: “Elegantly refined relief represents the purists and geometric direction in contemporary sculpture. With admirable simplicity of pure form and inventive use of highly reflective surfaces, he has created a work with the magic of changing patterns.”

Roy Gussow “The Flow of Water”

The museum curator called Gussow’s design a kaleidoscope with its reflective surface highly polished by the craftsmen in the finishing department of Medallic Art Company. Other pieces were given more customary patinas, where acids were employed to apply color and protective surface.

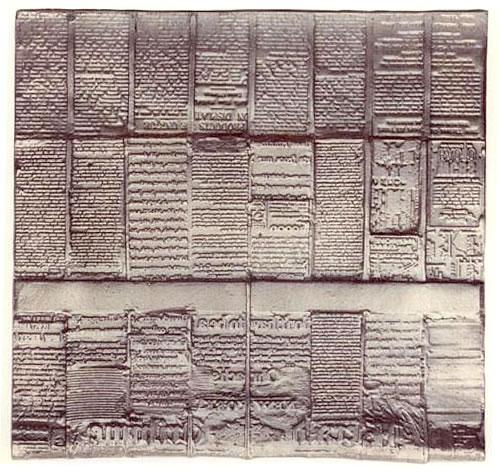

Chryssa’s piece was, perhaps, most unusual of all. It replicated the surface of lettering found in newspapers of the time, where metal lines of type were gathered in columns and a curved mat made for printing on high speed presses. Chryssa, whose full Greek name was Vardea Chryssa Mavromichaeli, cast her model using a method somewhat similar to printer’s technology.

Vardea Chryssa Mavromichaeli casting

For the seven artists their intent was to create a suitable relief. For the manufacture the intent was to render those reliefs in suitable medallic form as attractively as possible, Not one of them knew they had created an entirely new art form. Yet they had given birth to the medallic object.

Six months later, in France, where modern art is de rigeur, the Paris Mint issued its first item that could be termed a medallic object. Roger Bezombes, an accomplished medailleur, created in 1966 his first of what was to become a persistent passion for the new art form. It was a uniface piece bearing a portrait of Ceres, the goddess of the earth and agriculture, with open work for eyes and mouth.

Roger Bezombes “Star of Joy”

His most noted work, however, is Star of Joy, which Americans call Sunburst for its multiple sunrays. The 24 rays surround the sun in the center, polished and containing the lettering. In contrast, the sun’s rays are style rude, an art term meaning “rough style.”

Bezombes’ imagination embraced an unfettered creativity, wild and highly imaginative. He pushed the envelope in design, shape, spatial form, and the use of fabricated objects. He made occasional use of buttons and sea shells, and delighted in making large eyes with tiny balls as the iris.

He once designed a stork, fully upright, made of two dozen scissors. Another work was a light bulb where the filaments appear in multiple shapes and discs. For another he added eyeglass frames on an obverse portrait that morphs into – what is it? – a severed bicycle on the reverse.

Like Bezombes, other abstract artists were attracted to the new art form for its ease of replicating their highly imaginative models. Picasso made a medal of table spoons, another as a dinner plate.

Once the Paris Mint began producing these unconventional medals it attracted artists throughout Europe and even the Orient as their popularity spread among the coterie of world artists.

The new form was encouraged by one devotee fortunately in a position of influence: Pierre deHay, one-time director of the Paris Mint. During his administration modern art was welcomed to be rendered into medallic form, and these creative objects were produced in increasing numbers. At the peak of this phenomenon, during Director deHay’s reign in the early 1980s, the Paris Mint placed in production one new art medal a day, predominantly medallic objects!

By 1985 its collection had grown to the point where it needed a separate catalog. The minions at the Paris Mint gathered and photographed the work of 124 artists, mostly French; 302 items divided into three classes – medallic objects, plaquettes, and what they called medallic enrichies, a medal with added adornments.

But what to name this modern art form? They chose “medallic objects” as the catalog’s title – la Medaille-Object – the first time this term appeared in print. The term became accepted first by the artists, then by collectors and ultimately added to numismatic lexicography.

American artists, however, could not match the French pace. Among a handful of early medallic objects made in America was one by modernist Roy Lichtenstein, Salute to Airmail, in 1969. But what American artists did was to band together in 1982, forming the American Medallic Sculpture Association to encourage all forms of medallic creations. Previously, artists in England had formed British Art Medal Society in 1979, followed by artists in Canada who established the Medallic Art Society of Canada in 2000. Similar medallic organizations have been established in Europe, Japan, and elsewhere.

Exhibitions of these national societies embraced medallic objects, as did the world organization, the Fédération Internationale de la Médaille d’Art, everywhere reverently called “Feed-’em” for its FIDEM initials. Its international exhibits of recently created coins and medals are held every other year or so. For thirty years, that which had been conventional, typical, medals gradually became dominated by atypical medallic objects.

Two FIDEM congresses have been held in America, appropriately at the American Numismatic Association’s Colorado Springs headquarters. The first in 1987 attracted 694 artists from 25 countries. Well-known American sculptor Mico Kaufman created the official Congress medal, an avant-garde design in oval shape.

The second American FIDEM Congress was held in 2007 with exhibits from 576 artists representing 30 countries. A dramatic, innovative medal, issued by ANA, was created by New England artist Sarah Peters. It was perhaps the most innovative FIDEM Congress Medal ever! Bearing a human figure on both sides, male on one, female on the other, it was designed in modified quadrant shape where four could be interconnected together forming somewhat of a circle and rearranged in three other shapes.

The bulk of both of these exhibitions, like others nationally, prior and since, were unquestionably, medallic objects.

Just what are medallic objects? How would one define them? Medallic objects are modern art in medallic form. While inspired by the medallic genre they do not have the restrictions of coins or medals.

They must be permanent, capable of being reproduced, usually made of metal and, in most issues, have a shape other than round. Medallic objects break the rules of circular coin and medal design, go beyond any limitations, transcend any technical restraint, overcome medallic prejudice, in order to become interesting, aesthetic objects for the eye to behold.

Usually medallic objects are free-standing; infrequently called “standing medallic art.” But to stand alone is not even a requirement. They are not small statues, they are not upright or overgrown medallions – medallic objects are a new sculptural entity, indeed, that in fifty years has found its niche in the art and numismatic world.

The painter crafts his art in color and shadows. The sculptor crafts his art in forms and planes. The medallist crafts his art in relief and miniature size. But the creators of medallic objects, while they may be guided by the precepts of these graphic and glyptic arts, are not bound by restrictions of any art.

If I had to characterize their form I would say medallic objects are bas-relief unleashed. Their appeal will grow as collectors discover there are art objects in the field beyond coins and medals, yet inspired by what they have been collecting all along.

Satisfying a Medallic Artist

The late Harold Tovish

Sculptor Harold Tovish visited Medallic Art Company’s plant in New York City in 1965 to choose the finish of the 12-inch galvano of his relief that Art in America magazine called “Dehumanization of Mechanical Forms,” but what we called “Meshed Faces.”

The smaller medal was satisfactory, but he wanted the larger galvano to be different, the best art possible. Customarily the artist picks a patina color from the finishes that can be applied to a medallic item. While brown and green patinas are most common — the easiest to apply — virtually any color can be applied with different acids and different procedures. These are not paints nor coatings, these are permanent color of the metal itself

Toviah was more concerned with the surface texture than color. The satin surface of the wide rim enclosed a clear background and a pair of “faces” — all of smooth texture. Having all three congruent surfaces smooth is a no-no. It’s bad art in medallic sculpture.

As the master sculptor that Tovish was he wanted a texture on the background between the smooth rim and the smooth faces. It is good art to have contrast adjacent to or between two smooth surfaces.

The craftsmen in Medallic Art’s finishing department, notably the late Hugo Greco was assigned the task to satisfy Tovish no matter what. Give him whatever he wanted. With Tovish by his side Greco tried the usual techniques using chasing tools — dapple and matting punches — to apply the texture to the surface of the copper galvano.

Nothing he tried seem to satisfy Tovish. Greco tried tiny beads of acid to form minute incuse areas in the surface. Even that was unsatisfactory, it looked like the craters on the moon.

In desperation, Hugo picked up a beer-can opener, the kind with a hard metal curved point that leaves a triangular opening in the can. He starting scratching the surface in the background forming hundreds of small incuse circles and arcs. After a few minutes of this he raised the galvano above his head for better light. Tovish raised his head to observe the result.

“That’s it!” shouted Tovish.

Sources

- Objects of Desire by D. Wayne Johnson, The Numismatist, September 2007.

- Paris Mint, la Medaille-Object, 1985.

- FIDEM Exhibition Catalog, ANA, 1987.

- FIDEM Exhibition Catalog, ANA, 2007.

- Report From the 2007 FIDEM Congress, E-Sylum, September 23, 2007, volume 10, number 38, article 9.